Pandit Duraiswami aiyangar (1883-1956)

Early Life

Uthiramerur temple and the temple pond

he had to start his life on a truly clean slate. With no alternative, his sister and he spent the night outside the ancient Utharamerur temple – a beautiful edifice built during the Pallava reign. Both homeless and penniless, utterly without recourse, the two were literally no more than bits of flotsam in the vast sea of humanity, with hope of neither anchor nor harbour. But once more, the wheel of fate turned. A childless couple, a doctor of Ayurveda and his wife visited the temple. They saw the bright, intelligent face of the lad, the sweet innocence of the girl and enquired about them from the priest of the temple. He shrugged. There were too many itinerant beggars for him to keep tabs.

But the doctor was convinced otherwise. He went up to the boy and spoke kindly to him, enquiring about his background. On hearing of his immense misfortune, he and his wife made an instantaneous decision. They would take the two children under their wing. One does not quite know who was luckier – the little boy who received an unexpected guardian or the doctor who acquired an able assistant. For the lad’s curious mind and meticulous approach were just the right ingredients necessary to fashion a wonderful protégé. More than anything, Srinivasavaradhan was a sponge, absorbing everything that came his way. It was as if his soul yearned for knowledge and the more he studied, the greater grew his thirst.

Since the study of Ayurveda necessitated a knowledge of Sanskrit, he took to it, literally like fish to water, excelling in what was often referred to as the scholar’s language. Much later, his daughter, Vaijayanti would recount how he would learn languages by trying to decipher posters on walls, gathering known letters together to comprehend meanings of words, thus also pinning down unknown letters.

It must have been a mammoth effort, but for the lad, languages were a jigsaw puzzle he enjoyed unravelling and putting together. Thus he expanded his base, with Malayalam and Telugu following Tamil, his mother tongue. Even the little known Manipravalam, an ancient script version of Tamil combined with Sanskrit, soon became grist for his mill. And because he had to often communicate for official purposes with the British, English was just one more language in his ever growing kitty. All this without once entering the premises of a school!

The Professional Choice

Thus immersed in study, absorbed in aiding his guardian doctor at his practice, time flew on swift wings. By now, the tiny, uncertain Srinivasavaradhan had grown to be a confident, strikingly handsome boy with a personality that made heads turned when he walked on the road. Combined with this was the fact that he was a healer and the simple, illiterate poor who thronged to his clinic, admiringly addressed him as Durai, meaning master. Soon, the title swami, denoting respect, was added to it and Srinivasavaradhan morphed into Duraiswami, a name that would be his till the very end.

As an apprentice under the Ayurvedic doctor, Duraiswamy could have stuck to the straight and narrow, merely observing and learning how to diagnose and heal the patients who approached them. After all, the kind doctor had made it a point to truly educate his student in all the intricacies of the ancient system of Ayurvedic medicine. But for the ever-hungry Duraiswami, this was just the simple and basic part of medicine. He wanted to know more, to investigate further, to deepen his understanding and further his abilities.

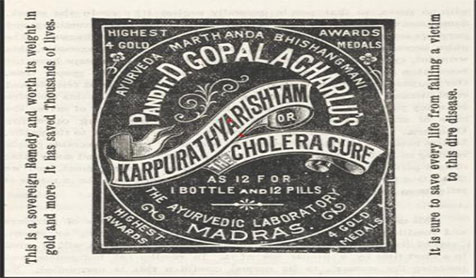

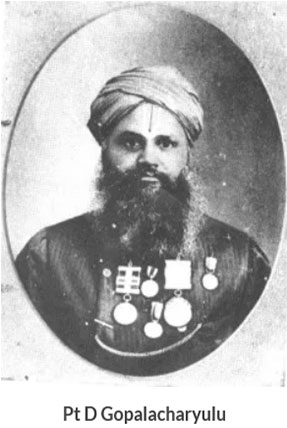

When the opportunity arrived he ventured out to Calcutta where he completed a 5 year course in Ayurveda and gained practical knowledge under Kaviraja Dwarkanatha Sen, all before he was 30 years of age. It was while he was here that he studied the Sanskrit texts that he translated in later years. Returning to his base in Tamil country, he began his clinical practice in Trichinopoly. Soon, such was his renown that he was invited by Prof. D. Gopalacharulu, founder of the Madras Ayurveda College to teach and work in the hospital attached to it.

But employment was only a small part of the world Duraiswami occupied. Self-motivated, pushing boundaries, discovering books, exploring concepts, coming to grips with ideas, this was an extraordinary intellect exploding with energy. Thus began his research into the human anatomy to which end he read books on medicine, both Western and Eastern in order to create his own combinations of medications to cure illnesses.

The Phenomenal Mind

While he cultivated an entirely scientific temperament, given to questioning, analysis and conclusions, there was another, more artistic side to his personality that blossomed beautifully alongside. It was this aesthetic hunger that found satiation in the works of the Sanskrit poet, Mahakavi Kalidasa. The dramatist and poet became such a major inspiration that he took to translating his works in Tamil so he could reach a much larger audience. At a mere twenty eight years of age, he translated Kalidasa’s Kadambari; at thirty, Meghsandesa.

His daughter, Vaijayanti often commented that while he constantly crushed powders and pastes in his mortar and pestle, he would also be perusing the plays of Kalidasa and composing his own commentaries on literary texts. On the one hand, he drew accurate figures of the human anatomy,on the other, he dove with equal passion into poetry and literature.

But Duraiswami’s restless mind constantly sought vaster pastures, newer arenas. Despite all his interests, it seemed that the soul of this man was still empty, devoid of sustenance. An intense spiritual longing filled him, prodding him to find a resolution. After all, he belonged to the deeply devotional sect called Aiyangars, the Sri Vaishnava Brahmins who followed the path of Vishishta Advaita taught to them by awe-inspiring acharyas like Sri. Ramanuja and Vedanta Desika.

And so it was the turn of philosophy and religion to come calling. Steeped in the traditions of his ancestors, Duraiswami plunged with zeal into an immersive study and translation of the works of the great Sri Vedanta Desika. His aim was to make his unique texts available to a far wider audience in Tamil. As we observe it, the trajectory was truly amazing.

From medicine to languages, from languages to literature, from literature to philosophy, the man and his mind were indefatigable. But while his sweep was vast, Duraiswami’s most significant quality was his unerring eye for detail. He was an embodiment of Michaelangelo’s statement, “Trifles make perfection, but perfection is no trifle.”

Just to illustrate the meticulous eye for minutiae this man possessed, an incident comes to mind. His insatiable appetite made Duraiswami consume all Sanskrit texts. But he was obviously deeply influenced by The Bhagavad Gita. Amongst his many papers collated after his death, was an edition of The Bhagavad Gita published by ‘The Rasashala Aushadashram’, Gondol, Kathiawad, India, 1941. What was so peculiar about this edition of The Gita? Thereby hangs a tale.

In his readings, Duraiswami found that Sage Vyasa had mentioned in the Bhisma Parvah (he notes down this source as well) that Sri Krishna had spoken 620 verses, Arjuna’s utterances were 57 verses, 67 verses were attributed to Sanjaya and Dhrithrashtra had to his credit 1 verse. Together, the author of The Gita had mentioned 745 verses in all. But most versions of The Bhagavad Gita have only 700 verses. Where were the missing 45 verses?

Duraiswami with his scholar’s instinct went chasing after them with a toothcomb. Enormous exploration later, he finally unearthed a rare manuscript, published by the afore-mentioned printing press in Gujarat which contained all 745 verses. In a handwritten note on his letterhead, enclosed within this copy is the explanation just offered. One can only marvel at a mind that was so concerned about accuracy that it laboured after even this small fact. For such a one, no concept was too vast to comprehend, no detail too infinitesimal to investigate.

It was obvious that for this exceptional individual, all knowledge was a playground in which he ran riot. Often lost in a world of imagination or engaged constantly in analyzing data, he was naturally hard put to keep the proverbial wolf from the door. That his children grew up with meagre resources was reiterated by all of them. His wife often complained of the lack of supplies and had to wage battles to satisfy the needs of her growing children. We are told that one quarrel lasted days, when she insisted she needed footwear to walk to the market, and he stubbornly refused to part with the measly amount required.

Despite the fact that the most affluent of businessmen came to consult him, Duraiswami was notorious for either forgetting to collect his fees or spending it on his innumerable academic projects that were often not remunerative and even demanded that he spend his own money. It was clear – while this man was a brilliant intellectual, the requirements of an ordinary life were completely beyond his grasp.

His Achievements as a Doctor

He was appointed teacher at the Madras Ayurveda College and thereafter an examiner for the Medical College Board Examinations at Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka) and Burma (present day Myanmar). Soon after the retirement of his mentor Pandit D. Gopalacharlu, Duraiswami was made chief physician of SKPD Trust’s free Ayurvedic hospital at George Town in Madras.

But merely studying, absorbing, learning, and diagnosing still felt insufficient. Naturally, almost seamlessly, Duraiswami’s research led him to begin a career in writing. Initially it took the form of articles to disseminate information to the layman on general well-being. But soon enough, his writings grew far more scientific as he published technical papers in ayurvedic periodicals. From writing, Duraiswami took the next step. He moved into publishing.

(Pt. D. Gopalacharyulu – from the autobiography of Dr. A. Lakshmipathy, courtesy: Rukmini Amirapu.)

He established Vaidya Kalanidhi Karyalayam through which he started to publish translations of medical texts such as Sarṅgadhara Saṃhithai, Aṣhṭaṅga Hṛudayam, Madhava Nidanam and Rasaratna Samuchchayam. He also started the Tamil medical journal, Vaidya Kalanidhi. In time, he was translating ancient palm-leaf manuscripts into Tamil and providing commentaries for published material.

When during his research Duraiswami chanced upon Anandaraya Makhin’s allegorical play Jivanandanam, it was just what his mental capacities hungered to feast on. He wrote an extensive commentary for it in Sanskrit. About this exercise of editing and writing a commentary to Jivanandanam he confessed, “I was obliged to write this exhaustive commentary, Nandini, which developed five to six times the size of the original text of Jivanandanam. To write this out completely, inclusive of some appendices I required more than five hundred foolscape sheets.”

Almost half a century later, Anthony Cerulli, an Italian scholar of Sanskrit who has worked extensively on the text, wrote in the introduction to the Malayalam edition, “The Jivanandanam of Anandaraya Makhin is a Sanskrit naṭaka or play that was produced sometime around the turn of the 17th to the 18th century in South India, during the reign of the Thanjavur Maratha king, Sahaji. The text also belongs to a select group of Sanskrit literature known in English as allegory.” Duraiswami’s extensive commentary was truly voluminous, well researched and probably the only way the multi-layered meaning of the original text could ever be understood!

Such is the relevance of the knowledge he imparted that his translation and commentaries, Ashtanga Hrudayam and Rasaratna Samuchchyam are used till today as respected Ayurvedic texts in colleges of education.

When he was bestowed with the position of the President of the Ayurveda Mahamandal, Duraiswami put together a corpus of core Ayurveda texts such as Caraka, Sushruta, Madhava Nidana, Aṣhṭaṅga Hrudayam, Bhavaprakasha, Sarṅgadhara Samhita, Rasaratna Samuchchyam, many of which he himself translated into Tamil. To enhance the competence of the students who studied under him, he made it compulsory to pass Sanskrit examinations at Visharath or Acharya levels to qualify and practice Ayurveda.

Although aware of the life enhancing and healing properties of the science of Ayurveda, Duraiswami was equally abreast of modern science, which was moving rapidly and inexorably in the direction of allopathy. So he decided to be a bridge. He published anatomical illustrations in his journal and at the same time, tried to equate Ayurvedic Sanskrit terms with modern anatomical phrases.

The Activist: The Challenge of Ayurveda to Western Medicine

This is something we must not forget as we uncover yet another facet of this magnificent personality. Along with his mentor, Gopalacharulu, Duraiswami worked tirelessly for the re-vitalization and re-establishment of Ayurveda as a viable system of health and healing. He realized all too well that the system was entirely flawed. When he looked within, he was extremely critical of the plethora of doctors who neither knew enough Sanskrit to read original texts, nor enough of the human anatomy to make an accurate diagnosis.

He bluntly expressed himself, “Presently, some are calling themselves Ayurvedic physicians after reading one or two medical texts or after learning preparation of one or two medicines. Most of them have not studied courses such as anatomy, diagnostic techniques, materia, medica, symptoms of diseases etc., through the institutions which teach Ayurveda, with the help of authentic Sanskrit texts. This is the main reason for the fall of Ayurveda.”- Vaidya Kalanidhi, (1918).

But this was not his only battle. We must remember that Duraiswami lived in tumultuous times. India was in the throes of its freedom struggle, fighting against English imperialism. While Duraiswami may not have participated in the political campaign, he was certainly waging another encounter of his own against the British. It was a combat against a government which arrogantly dismissed the entire edifice of Ayurveda.

All of this came to the fore when the British government in India appointed one Dr. Koman to investigate into the merits of Ayurveda. He presented a paper that called into question the very basis of Ayurveda as a science. It was intended to be the death knell of all Eastern forms of medicine, whether Ayurveda or Unani. But Duraiswami refused to take this insult lying down. He refuted each one of Dr. Konan’s allegations.

Writing a paper to counter his, Duraiswami argued, “Doctor Koman’s report has, with the object of ruining the Ayurvedic system, been framed in such a manner that the trade in English medicines in this country may be advanced and the western system of medicine may be deemed by our countrymen to be superior.” He made it clear that Indians were well aware that for the British, medicine far from being a moral or ethical commitment to heal, was merely a commercial transaction.

He further went on to question the competence of Dr. Koman either to grant a certificate of merit to Ayurveda or to decry it. He wondered how the doctor could have come to his conclusions without bothering to study the principles of Ayurveda or testing its efficacy through interaction with patients. As if driving the final nail in Dr. Koman’s coffin, he pointedly asserted that the British doctor had neither consulted eminent experts and heads of Ayurvedic associations nor sought assistance from learned Ayurvedic physicians for his report.

He concluded that one could expect nothing but a prejudiced report from one who was a servant of the government. When this paper was published in Vaidya Kalanidhi and Swadesamitran, it created quite a storm! Support and appreciation poured in and he was soon hailed as a leader in upholding India’s indigenous, holistic healing systems.

We can illustrate this just by one example, that of Shri D.V.Kanakarathinam who under the guidance of Prof G. Chandhrika of Pondicherry University completed a PhD Dissertation “Physicians, Print Production and Medicine in Colonial South India (1867-1933)”. He wrote with great admiration about the contribution of Pandit Duraiswami Aiyangar in highlighting the scientific basis of Ayurvedic medicine and his role in regulating the practice in South India through his vice-presidency and presidency of the ‘All India Ayurvedic Sammelan’.

If we have to understand Pandit Duraiswami’s activism, it has to be seen in the colonial context. During that period, Ayurvedic physicians felt a sense of insecurity, while the colonial state used Western medicine as a cultural force to establish superiority over Ayurveda in the public sphere. A number of protagonists, such as Ganga Prasad Sen, Gangadhar Ray and Gananath Sen in Bengal, Shankar Shastri Pade in Maharashtra, D. Gopalacharlu, Duraiswami Aiyangar, Achanta Lakshmipathi, Thriparangott Parameswaran Mooss, Paniyinpally Sankunni Varier, and many, many others were involved deeply in the re-vitalisation movement.

Unlike the West which was content to merely thrust its understanding on its colonies, which included India, the practitioners of Ayurveda got together to introspect and stem the rot within. They uncovered causes, even apart from the threat from outside, for the decline of their practice, (many of these already established by Duraiswami Aiyangar), such as the ignorance of practitioners, stagnation of knowledge and the non-availability of their medicines.

Adulation and appreciation

And so it was that slowly but surely, Duraiswami’s scholarship and expression began making their mark. When a translation of Sri Pancharatraraksa of Sri Vedanta Desika was published, Srinivasa Murti, an eminent scholar of Sanskrit wrote in his Introduction to the book, “It is difficult for me to find words to express my deep gratitude to Pandit Duraiswami Aiyangar for the superb manner in which he has performed this labour of love, and for the vast erudition, great enthusiasm and the incomparable devotion which he has brought to bear on the work of editing this publication. Sri Duraiswami Aiyangar bears with distinction the title of Sri Desika Darshana Durandhara bestowed upon him by learned pandits in recognition of his eminent services in spreading the message of Sri Vedanta Desika”.

The work was undertaken by him in the spirit of a pious devotee preparing a worthy offering to be lovingly placed at the feet of the master, Nigamanta guru (Sri Vedanta Desika) of hallowed memory. “Where jnana (knowledge and wisdom) worked in happy union with shraddha (reverence and faith) and bhakti (devotion) as in this case, the result was bound to be an offering well worthy to be placed at the feet of the Master, and so it has been, as discerning readers may have seen for themselves.” – Srinivasa Murti Further in The Introduction, Srinivasa Murti says (in page xxv) that this publication by the Adyar Library is a critical edition, wherein 6 palm-leaf manuscripts and 5 printed editions of the Pancharatraraksha were examined and collated. Besides, Pandit Duraiswami Iyengar and Pandit Venugopalacharya have given the source of around 95% reference verses quoted by Sri Sri Vedanta Desika. This is very important to the present day research scholars and students.

When Anthony Cerulli was asked to comment on Duraiswami’s commentary entitled Nandini on Jivanandanam, he was effusive in his admiration. “Aiyangar’s medical career is surely what brought him into contact with Anandaraya’s Jivanandanam. Thankfully, because he was truly a man of letters, not just a man of medicine, his commentary on the text is sensitive to the medical import of the work while at the same time exceptionally aware of the many trans-subject references interlacing all seven acts.

Without Aiyangar’s commentary, the Jivanandanam is a highly entertaining dramatic work. The humour is obvious on the surface, and the overt bhakti is also clear. With the guidance of Aiyangar, however, the depth of Anandaraya’s knowledge of medicine and bhakti becomes staggering. Add to that his handling of references to Arthasastra, Yoga, Alchemy, and Literature, and one cannot help but be dazzled.” (Preface to Jivanandanam, by Anthony Cerulli)

His titles

Duraiswami’s amazing output, varied and comprehensive, his involvement in causes, his interest that spanned a vast variety of subjects, could obviously not go unnoticed. Although his hardships were many and his obstacles constant, honours rained in on him. He was awarded the title of Vaidyaratna (Gem amongst doctors); Pandit (Scholar); Ayurveda Bhusana (Doyen amongst doctors), Ayurvedacarya (Teacher of Ayurveda) and Sri Desika Darsana Dhurandhara (a scholar of Swami Desika’s works).

He was also elected President of the All India Medical Association. But the crowning jewel was when he was selected to deliver the Keynote or Presidential Address at the All India Medical Conference held in Trivandrum, in the state of Kerala. It was then that he came to the notice not merely of people of Madras principality but of the entire Ayurvedic community all across India.

But while every achievement of his was laudable, the one thing that made him unique was that he was known as a scholar’s scholar. Dedicated, scrupulous in his desire to attain excellence, industrious beyond limits, it is believed that he was the first to create a glossary of words that could be referenced back into the book, an indexing system that must have been Herculean considering that it was done entirely manually. Today’s librarians with computer facilities are awe-struck by just this one achievement, monumental and magnificent in its scope and depth.

But why was this rare gem of a man not given greater universal recognition? The impediment, as we have already stated was monetary. It was this alone that prevented him from publishing on a mass scale. It was this that limited both his opportunities as well as his endeavours. And yet, today, incredibly his books have travelled where he could never have dreamt of setting foot. Across the globe from New York, Chicago, the Library of Congress, Washington, Paris, Berkley, Cambridge and even Oxford, libraries treasure his books as prized possessions. Yet, sadly, we still do not know the sum total of his achievements as many of his books and commentaries are yet to be traced.

The curtains fall

Considering how much was being squeezed into his days, how packed his life had been it was clear that Pandit Duraiswami Aiyangar’s candle was burning at both ends and had been doing so for decades. How then could it burn long? At a mere seventy three years of age, on 2nd Dec 1956, this awe-inspiring figure passed on. Such however was his reputation, that the then Governor of Madras, Sri Prakasham himself came to pay homage to him.

Today, as we, his grandchildren look back at his great legacy, as inheritors of his mantle of knowledge, we feel both proud and humbled. And hence, before this luminous light is lost to posterity, we have made an attempt to enshrine his memory. What greater tribute can we pay to the man, his personality and his works?